Increase in Pertussis Cases Observed in Spokane County

Posted Dec. 6, 2019. Past health advisories and alerts are archived for historical purposes and are not maintained or updated.

Current Situation

Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD) has observed an increase in reported pertussis cases in Spokane County residents.

- Twenty-four cases were reported in November, compared with three in October and eleven in both September and August.

- As of mid-November, Spokane had the second highest number of reported cases of pertussis in the state, second only to Clark County (Vancouver, WA-area).

- As of December 3, 86 cases have been reported in 2019.

- Half of the cases have occurred in school-aged children; however, infants and preschool aged children have also been disproportionately affected (19%) of cases.

- Cases have been identified in most school districts across the county.

- Four people have been hospitalized, two infants ≤3 months and two adults ≥75 years.

Actions Requested

- Suspect pertussis in patients with a clinically compatible illness, with or without known exposure and regardless of vaccination status. Test with PCR and consider treating prior to test results if clinical history is strongly suggestive or patient is at risk for severe or complicated disease. Early treatment is very important. Note: the turnaround time for LabCorp can be up to four days.

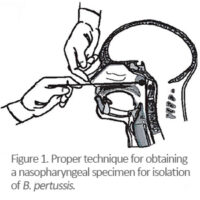

- Be aware of proper specimen collection: https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/clinical/diagnostic-testing/specimen-collection.html.

- Provide treatment to symptomatic household contacts and post-exposure prophylaxis to exposed individuals as recommended in the guidelines below.

- Advise patients to isolate until completion of antibiotic therapy.

- Recommend vaccination with Tdap or DTaP as appropriate, including Tdap during every pregnancy at 27 to 36 weeks’ gestation.

Post-exposure Prophylaxis Guidelines

- All household contacts and close contacts* (significant others, close friends) of PCR-positive cases.

- High-risk people exposed to a pertussis case. High-risk people are those who personally are at high risk of developing severe illness, or those who will have close contact with people at high risk of severe illness. These include:

- Infants, and women in their third trimester of pregnancy

- All people with pre-existing health conditions that may be exacerbated by a pertussis infection (e.g., immunocompromised people, those with moderate to severe asthma, etc.)

- People who themselves have close contact with either infants under 12 months, pregnant women or individuals with pre-existing conditions

- All people in high-risk settings that include infants under 12 months or women in their third trimester of pregnancy (neonatal intensive care units, childcare settings, etc.)

*Examples of close contact include direct face-to-face contact; an obvious exposure that involves direct contact with respiratory, oral, or nasal secretions from a case-patient (a cough/sneeze in the face, kissing, sharing eating utensils, etc.), and close proximity for a prolonged period of time (risk of exposure increases with longer duration and closer proximity of contact). Close contact does NOT include activities such as walking by a person or briefly sitting across a waiting room or office from someone.

If after assessing exposure it is not clear whether an exposure occurred, it is appropriate to encourage the exposed person to watch for signs and symptoms of pertussis for 21 days following their last exposure to a symptomatic person. These exposed persons should be instructed to seek healthcare immediately at the first sign of compatible illness.

About Pertussis

Pertussis, more commonly known as whooping cough, is a contagious, respiratory disease caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis. The illness is typically characterized by a prolonged paroxysmal cough that is often accompanied by an inspiratory whoop. Disease presentation can vary with age and history of previous exposure or vaccination. Young infants may present to a clinic or hospital with apnea and no other disease symptoms. Adolescents and adults with some immunity may exhibit only mild symptoms or have the typical prolonged paroxysmal cough. In all persons, cough can continue for months. Infants are at greatest risk for pertussis-related complications and mortality. The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) maintains a thorough overview of the clinical features of each stage of illness.

Early diagnosis and treatment of pertussis might limit its spread to other susceptible people. When pertussis is strongly suspected, attempts to identify and provide prophylaxis to household and other close contacts at high risk should proceed without waiting for laboratory confirmation.

Testing

Determining who has pertussis and who does not can be difficult, particularly during the catarrhal phase when symptoms can be indistinguishable from those of minor respiratory tract infections (coryza, low-grade fever, mild cough). Whenever possible, a nasopharyngeal swab should be obtained from all persons with suspected pertussis for PCR testing. A properly obtained nasopharyngeal swab or aspirate is essential for diagnosis. CDC has produced training videos on proper specimen collection.

Antimicrobial Treatment & Prophylaxis

Antimicrobial treatment does not generally lessen the severity of disease unless it is begun in the catarrhal phase, prior to paroxysmal coughing. However, early treatment reduces transmission and is essential for disease control. Persons with pertussis are infectious from the beginning of the catarrhal stage through the third week after the onset of paroxysms or until five days after the start of effective antimicrobial treatment.

The recommended antimicrobial agents and doses are the same for both treatment and chemoprophylaxis. Three macrolides are recommended by CDC for treatment of pertussis. Azithromycin is most popular because it is given in a short, simple regimen of one dose each day for five days. Full treatment guidelines are available from the CDC.

Vaccination

Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent pertussis. Babies and children should get five doses of DTaP for maximum protection. A booster dose of Tdap is given to preteens at 11 or 12 years old. Teens or adults who did not get Tdap as a preteen should get one dose. Pregnant women should also receive a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy in the third trimester.

Pertussis vaccines are effective, but not perfect. They typically offer good levels of protection within the first two years after getting the vaccine, but protection wanes over time. In general, DTaP vaccines are 80% to 90% effective. Among children who get all five doses of DTaP on schedule, effectiveness is very high within the year following the 5th dose – at least nine out of ten children are fully protected. There is a modest decrease in effectiveness in each following year. About seven out of ten children/adolescents are fully protected five years after getting their last dose of DTaP and the other three out of ten are partially protected – protecting against serious disease.

CDC’s current estimate is that in the first year after getting vaccinated with Tdap, it protects about seven out of ten people who receive it. There is a decrease in effectiveness in each following year. About three or four out of ten people are fully protected four years after getting Tdap.